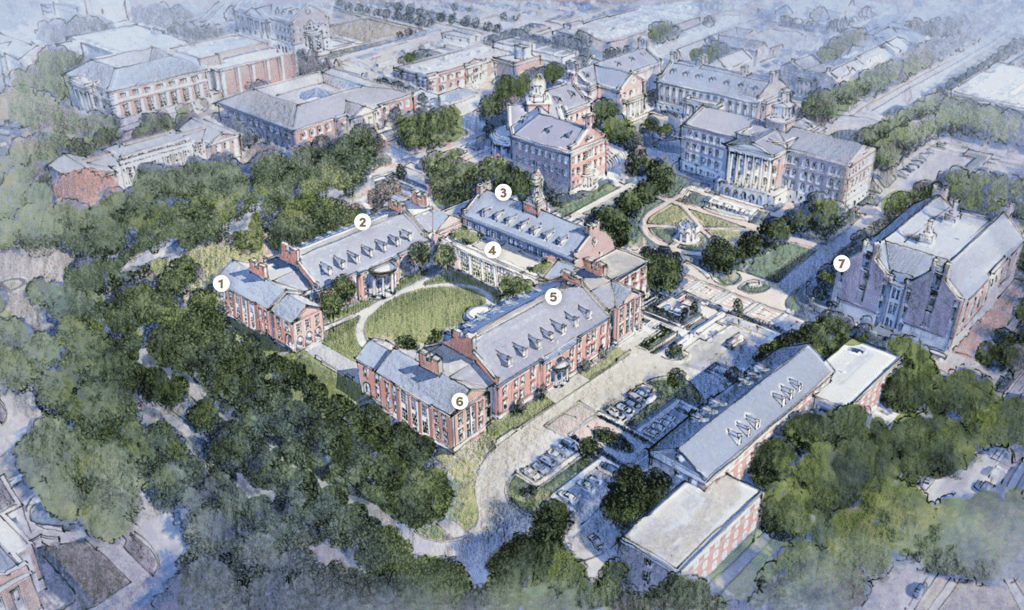

The Joseph Wylie Fincher Memorial Building, longtime centerpiece of the Cox School quad, was constructed in 1954 over a subterranean stream. Over the past half-century, flooding has not been uncommon. Bill Dillon, senior associate dean of the Cox School and the Herman W. Lay Professor of Marketing, came to campus one Saturday morning years ago after a particularly torrential few days of rain and found a Coke vending machine floating in one of the basement amphitheaters.

He cites other frustrations with SMU Cox’s facilities: technology limitations, inflexible workspaces, the occasional leaky roof. But, Dillon says, all these challenges underscore a broader reality: So much has changed about business education since the Cox School began staking its place on campus 100 years ago.

During that time, the School has evolved into one of the premier business education institutions in the country. If SMU Cox is going to continue to provide the kind of top-tier business education it has become known for, Dillon believes it will require a new facility that will embrace and adapt to a rapidly evolving business world. Matthew Myers, the ninth dean of the Cox School of Business, Tolleson Chair of Business Leadership and David B. Miller Endowed Professor in Business, agrees.

A Solid Foundation

SMU Cox’s growth began in the years after World War I, when the University first started offering business classes to supplement its traditional liberal arts-focused education. The growth of the business curriculum over the years came in fits and starts, says Myers.

“You saw an incredible growth in interest in business after World War II, when the GI Bill came in,” Myers says. “Then also in the 1970s, you saw a dramatic increase in the amount of interest in business education. And in the late 1990s, not long after [SMU President] Gerald Turner and my predecessor, Al Niemi, came in, the trajectory of the School just really took off, and the reputation and the level of national dialogue about the Cox School increased dramatically.”

In many ways, Cox’s current facilities mark these growth spurts. The first business classes were held in 1920 in Dallas Hall, and then in a freestanding wood- frame building for several decades. The Fincher Building came in 1954, followed by the Trammell Crow and Cary M. Maguire buildings in 1987. And while those facilities have helped incubate Cox’s remarkable growth — around 25% to 30% of students at SMU are Cox students — they were designed before incredible cultural and technological changes that have reshaped both the business world and business pedagogy over the past 30 years.

Now that business education is experiencing another defining moment, if Cox is to continue to serve as a national leader, it will need a new home that reflects that ambition.

“Since the mid-1990s, we have competed with some of the best business schools in the country,” Myers says. “We are in a very competitive sphere and in a place where the campus is increasingly dependent upon the high quality of programs and delivery of those programs. We have more demand, and we have to be able to meet that demand. And currently our facilities don’t allow us to do that.”

The Next 100 Years

What kind of facility could meet the needs of an increasingly dynamic and uncertain future? Cox leaders formed several administrator and faculty committees to begin the process of planning a new facility. They traveled to schools around the country that have opened new facilities, toured corporate workspaces and studied the emerging trends in business and education that might point to the pressing needs of the coming decades.

“What we have seen, and what will continue, is a move into industrial sectors outside of where we have been involved in the past.”

Cox School of Business Dean Matthew B. Myers

At the core of the project was a distinct challenge. A new building design could address many of the needs the current facilities don’t provide. But the new facility must also anticipate unknown future needs, including projected shifts in the local, national and global economies.

“We’re very much geared toward kind of the traditional workplace, in particular energy and retail,” Myers says. “What we have seen, and what will continue, is a move into industrial sectors that are outside of where you may have thought we would have been involved in the past.”

These sectors include technology, the digital economy and more entrepreneurial business practices. In recent years, Cox’s curriculum has evolved to meet these areas’ growth, but a new Cox facility could mean a physical environment that meets the need to train students for a more collaborative and technologically integrated work environment.

The new facility could provide classrooms that feature a more seamless integration of technology and more collaborative workspaces. The School’s location on campus means that a new Cox building design could facilitate greater interaction, not only between faculty and students within the Cox School, but also between other colleges and faculties at the University.

“We want to break those barriers down,” Myers says. “We want to be able to ensure that the type of interaction takes place that would take place in any business that’s facing the same sort of multidisciplinary problems and the need for solutions beyond those traditional same marketing and finance and accounting borders.”

A future home for Cox would not only offer an innovative approach to classroom space but also serve as a recruiting tool, both for students and faculty Cox hopes to attract as well as for business partners that have become increasingly integrated into the Cox education experience, both through collaborative projects and business community networking events.

“That never occurred back in the 1990s and the 2000s — there was never that level of intimacy between the [corporate] strategic partnerships and the students themselves,” Myers says. “I think when we were looking at what the facilities should look like and what we wanted to imitate and what we wanted to emulate, what we wanted to include was what we’ve seen out there in the marketplace. We spent a lot of time talking to our corporate partners as well. We spent time in Austin and here in the Dallas-Fort Worth area to see where they have changed, what the workplace looks like and what their expectations were for interaction and capability of their new hires.”

Imagining the Next-Era Classroom

There was no way that in 1987, when the Crow and Maguire buildings opened, administrators could have anticipated the seismic changes that have reshaped the worlds of business and education over the past 30- plus years. So how can a new building opening in the third decade of the 21st century be ready for whatever reshaping of the business landscape will surely take place over the coming decades? For Senior Associate Dean Dillon, the answer is all about designing a space that can be both dynamic and flexible.

“That’s the challenge any new building faces: How can you get a line of sight into how things might be changing 10 years from now?” Dillon says. “So when we choose technology, the question is, what is its capacity for change? How easy will it be to change it? We’ve had some of those discussions with classrooms. How easy will it be to change a classroom into something else?”

There are some clear changes Cox planners would like to see made to the educational spaces within the new facility. These include a move away from more auditorium-style classrooms toward what Dillon calls “cluster classrooms,” where students’ desks can swivel and lecture halls can morph into collaborative workspaces. Myers says that, taking a page out of Carnegie Mellon’s playbook, they plan to provide “makerspaces,” which will allow more cross-disciplinary collaboration between business students and science and engineering students, fostering an entrepreneurial capacity for developing new products and processes within the curriculum.

The recent experience adapting to virtual learning during the COVID-19 pandemic has only reemphasized the need to create classrooms that provide the best educational experience for both in-person and distance learning. Dillon says Cox’s launch of the Online MBA program helped prepare faculty and administrators for taking education online, and the new facility will have in-classroom technology that will allow for a more seamless and engaging virtual experience.

But rather than trying to predict what future tech- nological, business or pedagogical needs may look like, Myers says the new facility planning is driven by a singular principle: to create a space that can incubate the “9-to-9” model of business education.

“In other words, the students come into the building and they start at 9 o’clock and then might spend the entire day there,” Myers says, “whether it’s going to classes or interacting with faculty and other students, particularly with study groups and project groups. Even on their downtime, they are spending time there. What was really impressive to me when we traveled around the country to look at a lot of the schools that we’re competing with, like Wake Forest, Tulane, Wash. U., USC and others, was that sense of community. It was one of the common denominators of their facilities.”

That sense of community, along with technological innovations and cutting-edge design, will lead the Cox School into the second 100 years of business education at SMU.

The New Building Wish List

- More seamless integration of technology

- Multidisciplinary opportunities

- Dynamic and flexible spaces that can be adapted

- Clusterclassrooms instead of auditorium-style

- Lecture halls that morph into collaborative workspaces

- Enablement for in-person and virtual learning

- Event spaces and opportunities for corporate strategic partnerships between students and the business community

- Features that train students for the new workplace