We live in a time of information overload. Two or three million articles get published every day. More than 500 hours of videos upload to YouTube and 350,000 tweets post on Twitter every minute. And this is just scratching the surface. Ultimately, the average adult makes about 35,000 remotely conscious decisions daily—and all it takes to influence those decisions is a subtle change in how information is presented.

Milica Mormann has devoted her academic career to teaching and conducting research in an area of great academic interest and profound social importance: understanding how the presentation of information influences human decision-making.

In May, the SMU Board of Trustees promoted Mormann from assistant to associate professor of marketing with tenure.

Mormann’s passion for understanding when and why we pay attention to certain information has far-reaching implications. After all, the way we perceive and process information directly influences our behavior and, therefore, how we live our lives.

Her work, which equips consumers, businesses and policymakers to battle ever-shrinking attention spans, has been featured in The Wall Street Journal and Harvard Business Review and published in peer-reviewed journals including Trends in Cognitive Sciences and the Journal of Consumer Research. The latter recently published research she co-authored with colleague Matthew Fisher on “The Off by 100% Bias: How Percentage Changes Greater than 100% Influence Magnitude Judgments and Consumer Choice.”

In the classroom, Mormann draws on her research to better help marketing students understand human behavior.

We asked her what trends she’s observed and what they indicate about our future.

Q: What drew you to study how we make decisions? How did that decision come about?

A: When I was going through my Ph.D. courses, I read an article on attention by a famous marketing professor, and I was instantly hooked. To my surprise, very little research was done on this important topic at the time. There were very few studies on attention in the domain of consumer behavior or in the broader literature on decision-making—partially because it was hard to study. I liked that to study attention you had to integrate insights from different fields to create an interdisciplinary perspective. So, I looked at psychology, economics and business literature; that’s how attention became a central theme in my research. Fun fact: The famous professor whose work inspired me to pursue this topic and I have recently co-authored two articles on attention.

Q: How would you describe your teaching style? Does your research influence how you teach?

A: My classes are very interactive. I aim to leverage insights on behavior and decision-making, whether from a consumer, manager, investor or policymaker perspective, to enhance the students’ learning experience.

The paramount objective underlying all my teaching is to help students learn how to learn. We do not use electronics in class—no laptops, no cell phones—unless we are doing some hands-on data analysis. It’s really to get students to improve their critical thinking and learning skills. We can, and should, teach basics and frameworks, but it’s really important, long-term, that as students start their careers, they can pivot and excel regardless of the topic, software or tools they encounter.

Q: Technology and marketing have evolved so dramatically in recent years. What trends have you observed regarding attention or decision-making as a result?

A: TV commercials used to last 60 seconds, then 30, then 15—and now they’re down to 8. There’s this idea that people only pay attention for 8 seconds, so we’d better communicate the message in that time. Prevailing thinking has us almost down to zero-second attention. It’s so easy to swipe to another platform or switch to another device. So, research now asks: How, in zero seconds, can you grab and hold someone’s attention? In academia, we’ve tried to think of key underlying principles for how people perceive information that can be applied to many real- world contexts. And I’m sure companies use these findings to manage attention and ensure that consumers stay engaged, whether with a YouTube ad or a website.

Q: How do you apply your observations on attention to real-world situations?

A: You can study attention at a very basic level—for instance, the influence on attention of different swatches of color. This is what most research used to be and is how we learned about attention. What’s really fun for me is taking that and applying it in real-world domains. Instead of using red rectangles, I use KitKats and M&Ms—and that’s more realistic, because you’re not just studying the color. We show that elements of marketing such as packaging color or store shelf lighting can sizably influence shoppers’ decisions and, thus, impact profit in competitive marketplaces. Couching the research in real-world domains helps us understand not only how attention works but also these insights’ relevance across a variety of practical applications.

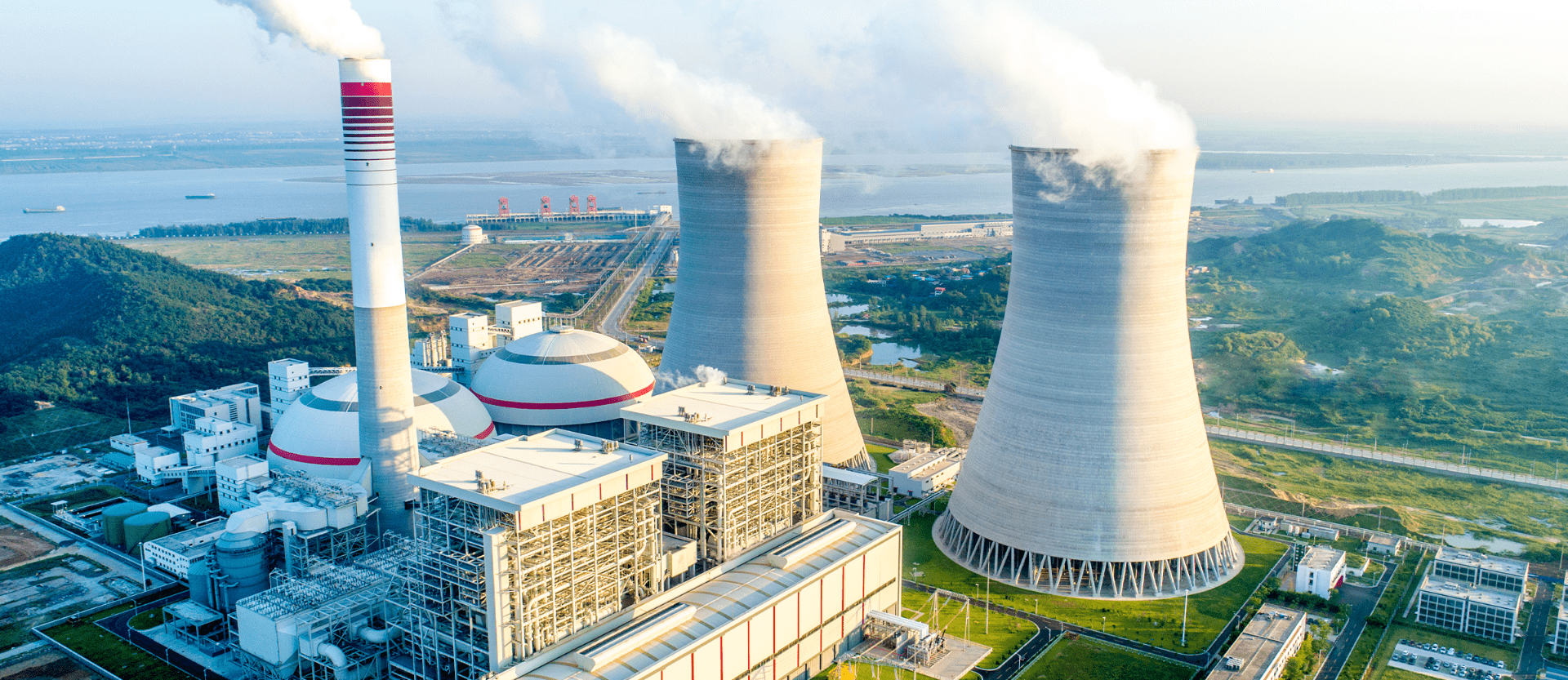

I also study questions such as how we can help people save more for retirement or how we can encourage more climate-friendly behaviors. My research has found that adding a favorable climate rating to performance metrics for investors to consider significantly increases investment in a company’s stock. Importantly, the magnitude of this effect depends on the framing and format, from wording to the colors used.

It is deeply gratifying to look at these issues from multiple stakeholder perspectives, including consumers, corporations and policymakers. In such contexts, everyone stands to benefit from a better understanding of what we pay attention to and how this influences our behaviors.

Q: What else do you love about your work?

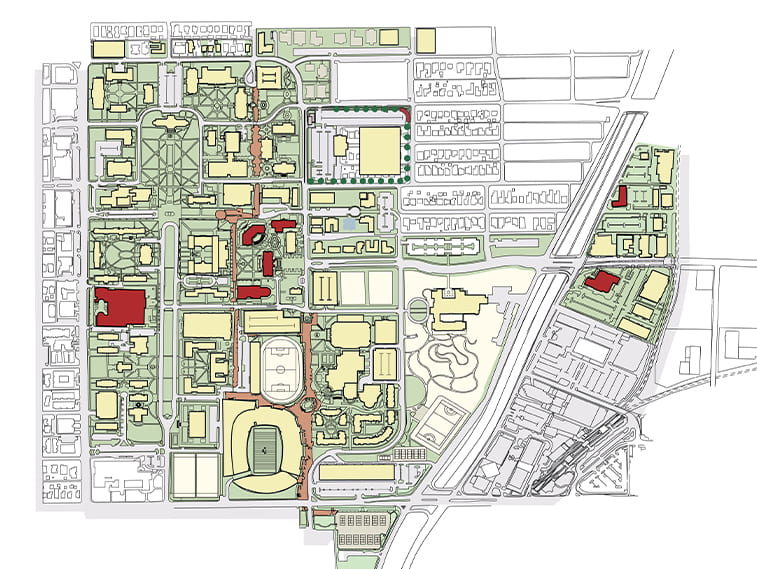

A: I feel incredibly fortunate to be at the Cox School of Business. It fosters a supportive environment that requires and enables faculty to excel in both teaching and research. Everyone is so positive and is part of a wonderfully collegial culture, which is what I really like about the school. While going through building construction and having no office for two years, we have still managed to have everything run smoothly, and there’s still a camaraderie among colleagues. I frequently refer to the business school as “my happy place” and point out to anyone who will listen, students and colleagues alike, just how privileged we are to be part of such a special community.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.